Take a look at any soccer game from the 1950s or 1960s. It doesn't matter which one. Any old game will do. You'll notice two things: how slow and sloppy the play is, and the likely abundance of goals.

For instance, revisit the final of the European Cup (the Champions League's predecessor) between Real Madrid and Benfica in 1962. This is considered a classic game, between two of the all-time great club teams, featuring several of the sport's early stars -- Alfredo di Stefano and Ferenc Puskas for Real and Eusebio for Benfica. The final score was etched into the cup as 5-3 to Benfica, a perfectly normal score in those days. Watching the highlights, it would seem any modern low-level team could beat either side.

For instance, revisit the final of the European Cup (the Champions League's predecessor) between Real Madrid and Benfica in 1962. This is considered a classic game, between two of the all-time great club teams, featuring several of the sport's early stars -- Alfredo di Stefano and Ferenc Puskas for Real and Eusebio for Benfica. The final score was etched into the cup as 5-3 to Benfica, a perfectly normal score in those days. Watching the highlights, it would seem any modern low-level team could beat either side.

It's hard to argue against the suggestion that soccer skill has become much more sophisticated since the days of Puskas and Eusebio -- no matter how stubbornly the stars of yore contest that the game has evolved. This marked technical evolution runs parallel to the indisputable fact that scoring has decreased significantly over the decades, a discrepancy that seems counterintuitive -- except that the art of defending has also made great strides.

Over a 52-year span, when the most progress was booked, scoring at World Cups -- a fair barometer for the state of the game, as our numbers show -- declined by more than half. In the first four editions of the tournament, from 1930 to 1950, scoring hovered around four goals per game (GPG), spiking at 4.7 in France in 1938. Since 1954, when scoring reached a high-water point of 5.4 goals per game, scoring has steadily decreased. The all-time low came in the 1990 World Cup, when a GPG of 2.2 was set in a tournament played, perhaps tellingly, in Italy, and won by Germany, the two countries traditionally known for having the most defensive approach in the world.

Scoring increased to 2.71 GPG in 1994, but during the past three World Cups, in 1998, 2002 and 2006, scoring declined from 2.67 GPG to 2.52 and 2.30 respectively.

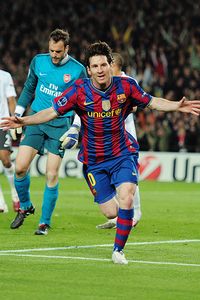

Surely now, if ever, is the time to buck this trend. The world's best forwards are all in the form of their life. Portugal's Cristiano Ronaldo, despite an ankle injury, has scored 25 goals in 28 games this season, with 18 of those coming in just 22 Primera Division contests for Real Madrid. Argentinian Lionel Messi has scored an astonishing 38 goals in 43 games for Barcelona in all competitions. Wayne Rooney, while hobbled by an injury at the moment, has notched 26 in 29 Premiership games, and 34 net bulgers in total. Ivory Coast and Chelsea striker Didier Drogba has 39 under his belt for both teams, while Real and Argentina attacker Gonzalo Higuaín has 24 in just 25 league games.

This barrage of goals by some of the world's finest is not a series of outliers in an otherwise unremarkable set. Scoring in soccer's elite leagues has risen collectively, not just among the most talented players. The English Premier League looks set to log a GPG of 2.79 this season, a number not topped in any World Cup year since 1965-66 and matched only in 1985-86.

If you collate the collective scoring figures of the four biggest -- read: richest and most popular -- leagues in the world (the EPL, the Italian Serie A, the Spanish Primera Division and the German Bundesliga) there is an irrefutable correlation to scoring at World Cups. While the aforementioned World Cup GPGs went from 2.67 to 2.52 and then 2.30, the four leagues' collective GPG went from 2.81 in 1997-98 to 2.5 in 2001-02 to 2.28 in 2005-06. This season, however, their collective GPG is up to 2.48, fueled primarily by the EPL's scoring bonanza. Here are the complete totals:

So what does that suggest with regards to the upcoming World Cup?

Taking the four biggest European leagues, as a representative sample size, it suggests a very discernable corner has been turned on scoring, implying that this World Cup will see more goals than any of the previous three editions.

That trend is corroborated by another predictor: goal scoring in the Champions League, a competition -- by virtue of being the premier club league tournament in the world -- manned with more World Cup talent than any other. Like the four big leagues, the Champions League also saw a drop in scoring over the past three World Cup years, going from 2.81 to 2.50 to 2.28. The Champions League, too, has witnessed an increase in goals this year. With just five of 125 games left to play, the current tournament has seen scoring rise to 2.48, a 0.20 upswing compared with the last World Cup year.

So -- gamblers of all ilk looking to cover a spread, take note -- how much then will scoring increase?

If World Cup scoring retains its close relation to Champions League scoring (as it often has: in 2001-02, CL games had a 2.50 GPG while the 2002 World Cup posted a 2.52 GPG; the 2005-06 CL stood at 2.28 GPG compared with the 2006 World Cup's 2.3 GPG), scoring is projected to be up by 9 percent, or 13 goals in total, which works out to an extra goal in just under every fifth game, or a rise from 2.30 GPG in 2006 to 2.58.

If this summer's soccerific event follows instead the direction of the four big European leagues, we'd see an additional goal every nine games. In that case, scoring would go up by 5 percent, or seven goals in total, good for a GPG of 2.48.

While these numbers hardly seem worth fussing over, they do have sufficient empirical evidence underpinning them to suggest that this isn't an aberration, if not yet a guaranteed omen that soccer is about to embark on a new era.

While ESPN soccer analyst Alexi Lalas concurs that goal scoring could go up at the World Cup, he believes it would be for reasons other than the scoring mindset of players like Messi and Rooney. "My reasoning for why [a rise in scoring] will happen has much more to do with the climate in South Africa being much more conducive [to scoring] than any other World Cup in memory. It's winter when the World Cup will be played and the temperatures will be low. We've had World Cups in climates that have been incredibly hot for decades now. It really affects the quality of the game and the number of goals that are scored. So if goal scoring goes up that will be a huge part of the reason why. Weather plays a big, big factor in a lot of these games."

Lalas, a veteran of the 1994 World Cup for the U.S., isn't convinced an upward trend in scoring would be maintained after this World Cup, though. "I still think the defensive posture and the tactics that have been implemented over the past decades are enough to keep the scoring down," he said. "The size and strength of abilities of goalkeepers, coupled with the increased pressure that then translates to a lack of courage and willingness to take risk, even on some of the bigger teams, is what ultimately has led to the dramatic decrease in goals."

The way baseball had a dead-ball, live-ball, steroids and, now, post-steroids era, soccer too has lived through stretches in which the way the sport is played has pivoted. From 1930 through 1954 scoring was steadily on the rise. In the time frame since, scoring has become progressively more rare. That second period was caused by, or led to, depending on your perspective, a gradual change in tactics, going from a commonly accepted lineup of four or five dedicated attackers to today's widely used system that prefers to field only one all-out striker.

With the latter approach is in no danger of dying out, some are skeptical of a return to the scoring ways of decades past.

"Most clubs in Europe play in physically demanding leagues and [players] then have to recharge for a tournament they have to play in. You're seeing a lot of strikers getting injured in the last phase of league play," said Ruud Gullit, a two-time World Player of the Year who played in the 1990 World Cup for the Netherlands as a forward. "Soccer has become harder and harder, and is always demanding more energy, which is just making a lot of players very tired."

"I don't see goals going up," Gullit added. "Players are so tired after such a long season. And the skill level has risen, players have become much more athletic, much more powerful and that takes a lot out of them, which can cost them at a World Cup."

If the statistical prediction for an uptick in goals in South Africa does materialize, it isn't yet indicative of a new approach to the sport. There have been upward outliers at the World Cup before (in '70, '78, '82 and '94 scoring crept up slightly, but the overall downward trend persisted). It is, however, an indicator that an overhaul of the way the sport is played is a possibility. The march of goals would have to be sustained over several World Cups to be statistically representative, not to mention noticeable to the naked eye.

For now, if nothing else, it'll be nice to see a few more goals being scored.

- Octopus Paul v Ahmadinejad [28/07]

- France suspend entire World Cup squ [24/07]

- Webb says World Cup final was taint [23/07]

- Goal-line technology off Fifa agend [20/07]

- World Cup final ball sold for £48K [18/07]

- Evra 'is being victimised', says Fe [17/07]

- Scolari says no offer yet to coach [16/07]

- Beckham: England players must take [15/07]

- Messi says WCup loss left him with [15/07]

- Now it's Brazil's turn to get ready [15/07]

| Years | Winners | Runner-up | Third place |

| 2006 | Italy | France | Germany |

| 2002 | Brazil | Germany | Turkey |

| 1998 | France | Brazil | Croatia |

| 1994 | Brazil | Italy | Sweden |

| 1990 | Germany | Argentina | Italy |

| 1986 | Argentina | Germany | France |

| 1982 | Italy | Germany | Poland |

| 1978 | Argentina | Holland | Brazil |

| 1974 | Germany | Holland | Poland |

| 1970 | Brazil | Italy | Germany |

| 1966 | England | Germany | Portugal |

| 1962 | Brazil | Czech | Chile |

| 1958 | Brazil | Sweden | France |

| 1954 | Germany | Hungary | Austria |

| 1950 | Uruguay | Brazil | Sweden |

| 1938 | Italy | Hungary | Brazil |

| 1934 | Italy | Czech | Germany |

| 1930 | Uruguay | Argentina | America |